How a Bill Becomes a Law

A Step-by-Step Refresher

Introduction of a Bill

Anyone may draft a bill, however, only members of Congress can introduce legislation, and by doing so become the sponsor(s).

There are four basic types of legislation:

- Bills: Proposed legislation introduced in either the House or Senate that must be approved by both chambers and signed by the president to become law.

- Joint resolutions: Resolutions which must pass both the House and Senate and receive the president’s signature to become law.

- Concurrent resolutions: Resolutions which must pass both the House and Senate but are not signed by the president and do not become law.

- Simple resolutions: Resolutions which are passed by only one chamber of Congress and do not become law.

The official legislative process begins when a bill or resolution is introduced and given a number (e.g. H.R. 1279 or S.2819) – H.R. signifies a House bill and S. a Senate bill. The bill is referred to a committee and printed by the Government Printing Office.

Step 1: Referral to Committee

With few exceptions, bills are referred to standing committees in the House or Senate according to the issues in the bill. This is done according to carefully delineated rules of procedure. Bills may be referred to more than one committee if the bill covers issues which fall under the jurisdiction of multiple committees.

Step 2: Committee Action

When a bill reaches a committee it is placed on the committee’s calendar. A bill can be referred to a subcommittee or considered by the committee as a whole. It is at this point that a bill is examined carefully and its chances of passage are determined. If the committee does not act on a bill, it is the equivalent of killing it. Committee heads have broad authority to determine a committee’s agenda and whether or not a bill is addressed.

Step 3: Subcommittee Review

Often, bills are referred to a subcommittee for study and hearings. Hearings provide the opportunity to put on the record the views of the executive branch, experts, other public officials, supporters and opponents of the legislation. Testimony can be given in person or submitted as a written statement.

Step 4: Mark Up

When the hearings are completed, the subcommittee may meet to “mark up” the bill, that is, make changes and amendments prior to recommending the bill to the full committee. If a subcommittee votes not to report the legislation to the full committee, the bill dies.

Step 5: Committee Action to Report a Bill

After receiving a subcommittee’s report on a bill, the full committee can conduct further study and hearings, or it can vote on the subcommittee’s recommendations and any proposed amendments. The full committee then votes on its recommendations to the House or Senate. This procedure is called “ordering a bill reported.” Again, the committee can kill a bill by voting against recommending it to the House or Senate or by not holding a vote on the bill.

Step 6: Publication of a Written Report

After a committee votes to have a bill reported, the committee chairman instructs staff to prepare a written report on the bill. This report describes the intent and scope of the legislation, impact on existing laws and programs, position of the executive branch, and views of dissenting members of the committee.

Step 7: Scheduling Floor Action

After a bill is reported back to the chamber where it originated, it is placed in a chronological order on the calendar. In the House there are several different legislative calendars, and the Speaker and Majority Leader largely determine if, when, and in what order bills come up. In the Senate there is only one legislative calendar.

Step 8: Debate

When a bill reaches the floor of the House or Senate, there are rules of procedures governing the debate on legislation. These rules determine the conditions and amount of time allocated for general debate.

Step 9: Voting

After the debate and the approval of any amendments, the bill is passed or defeated by the members voting.

Step 10: Referral to Other Chamber

When a bill is passed by either the House or Senate it is referred to the other chamber where it usually follows the same route through committee and floor action. This chamber may approve the bill as received, reject it, ignore it, or change it.

Step 11: Conference Committee Action

If only minor changes are made to a bill by the other chamber, it is common for the legislation to go back to the first chamber for concurrence. However, when the actions of the other chamber significantly alter the bill, a conference committee is formed to reconcile the differences between the House and Senate versions. If the conferees are unable to reach agreement, the legislation dies. If agreement is reached, a conference report is prepared describing the committee members’ recommendations for changes. Both the House and Senate must approve of the conference report.

Step 12: Final Action

After a bill has been approved by both the House and Senate in identical form, it is sent to the President. If the President approves of the legislation he or she signs it and it becomes law. Or the President can take no action for ten days, while Congress is in session, and it automatically becomes law. If the President opposes the bill he or she can veto it; or, if no action is taken by the President after the Congress has adjourned its second session, it is a “pocket veto” and the legislation dies.

Step 13: Overriding a Veto

If the President vetoes a bill, Congress may attempt to “override the veto.” In both the House and Senate, overriding a veto requires a 2/3 majority of those present and voting. If the House and Senate each vote to override a veto, the bill becomes law.

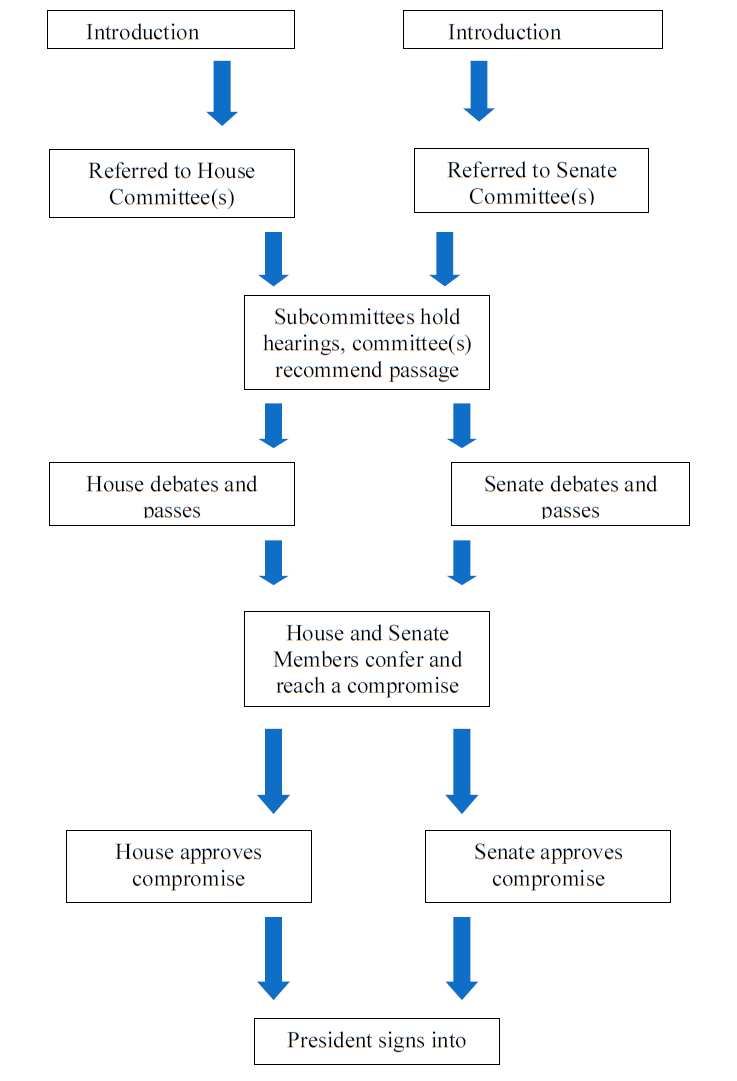

The Process, Visualized

The image below depicts a flow chart of the journey legislation takes on its way to becoming law.